It comes as no surprise that whisky’s origins are hotly disputed across the British Isles. Both Ireland and Scotland fly the flag claiming the honour of first capturing and distilling her beauties, but both seem to have lost all evidence of proof of their claim stake. Some master researchers say its origins date back as far as 800AD and link it to an Arab Chemist who was distilling the liquor, while translated medical texts suggest secrets of the distillation process came from doctors in Britain. As they served both Ireland and Scotland, the mystery remains unsolved.

In Great Britain, the cold, wet conditions made her a very poor greenhouse for grape growers that provided the perfect environment for whisky’s production. Distillers resorting to grain mash mastered the technique around the mid 1200s. King James IV, thought to be a father of widespread whisky production, sent a royal order for a large amount of malt, to make ‘aquavitae’. This term, of Latin origin meaning alcohol or again, the ‘water of life’ was commonly associated with whisky at the time.

In the mid 1500s, the intervention of an English king, the infamous Henry VIII who destroyed the monasteries, left many monks at a loss until they realised they could turn to their ancient art of distilling to make a living. Unwittingly, his dissolving of the monasteries did not dissolve the beverage’s future, instead providing the perfect conditions for the malt to ferment.

Back in Northern Ireland, the Old Bushmills Distillery was licenced in 1608 and still remains the undisputed record holder of the oldest licenced distillery in the world. By 1725, the English Malt tax fell so heavily on distilleries that the majority of the Scottish distilleries began to operate illicitly at night, when the hazy darkness hid the smoke from sight, lending the drink the nickname ‘moonshine’.

Smuggling became the order of the day for the next century and a half with excisemen known as gaugers fighting the highland farmers for whom it was the secret to their profitable livelihoods. In fact, despite their love of the poet Robbie Burns, the Scots were not so warmed to him initially. He trained as an exciseman before turning to writing some of the country’s most embraced poetry, including an ode to the spirit of Scotch.

Around this time the Duke of Gordon’s conscience was kicking him. On his lands a huge amount of the liquor was being produced. He drummed up the courage to make a proposition to the House of Lords that the government should make it profitable to produce whisky legally. It was a risky move but paid off handsomely. In 1823 the Excise Act was passed, which licenced the distilling of whisky in return for a fee of £10, and a set surcharge per gallon of proof spirit. The smugglers’ days might have been over, but their havens lived on. Many of today’s distilleries are still sited on the same once secret locations.

But the palate of the nation was adjusting. The lure for a lighter whisky on the tongue led to the creation of grain whisky, which, combined with potent and fiery malts, broadened the market of drinkers considerably. The bounds of the British Isles were proving too binding for the distillers. Famous names such as Johnnie Walker, James Chivas, James Buchanan and Tommy Dewar were not prepared to see the rest of the world go thirsting. They took their liquid gold to far away lands, expeditions paved in the routes of the British Empire and suppers as far away as Hong Kong to Cape Town began to crave the malted tones of their finest makings.

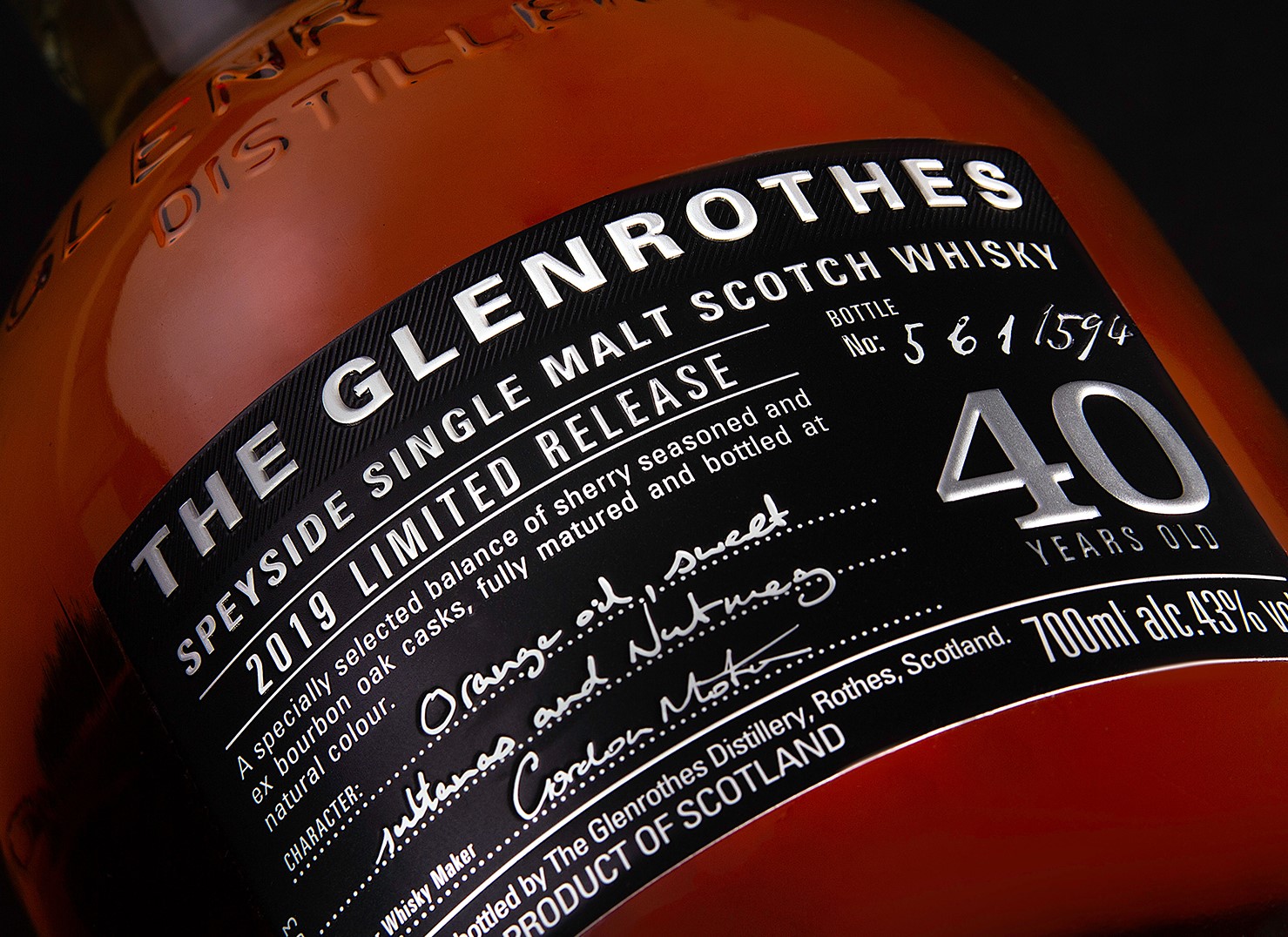

In recent decades, with competition rife in the marketplace, and class of spirit and bottle design going neck and neck, whisky packaging has come into its own. Collectors and designers agree that a good whisky in an uninspiring bottle is likely to be overlooked; gift buyers look for that work of art that shows the distiller has put personality not only into the drink but into every aspect of the finished product.

For many years a bottle was just a bottle with a label on to define its author. That was, until innovators such as Glenfidditch shattered their mould in 1961, in favour of a standout triangle shape instead. It was an outstanding success in terms of sales revenue, so other marketplace contestants were quick to follow. The highly acclaimed Glenfarcas Pagoda Sapphire Reserve, featuring 36 sapphires in its hand blown 30% lead crystal decanters with its intricate guardian lion engravings would surely not be worth the excess of £23,000 that values these bottles today were it not for the finest packaging.

We’d love to find out more about your product or brand and we’d be delighted to arrange a consultation to discuss your product embellishment needs – simply fill in the form and we’ll be in touch.

Alternatively, give us a call on 01733 396080